EXPERT INSIGHT

Breaking Down 3D Printing Barriers: It Takes a Community

The Materialise World Summit is an event organized every two years by Materialise. The main goals of the summit are to spark conversations between all stakeholders in the additive manufacturing industry, inspire innovations involving 3D technologies and create awareness of how versatile and valuable they can be.

A very present topic in Medical 3D Printing is the regulation and cost of 3D Printing and its use in hospitals. At the summit, we had the pleasure of hosting a panel discussion revolving around this subject.

The discussion was moderated by Prof. Jos Vander Sloten, a professor of biomechanical engineering at the KU Leuven, Belgium. He introduced five speakers, each an expert their field.

The speakers

Dr. Jonathan Morris

Dr. Thomas Schouman

Brigitte de Vet

Dr. Aalpen A. Patel

Erik Vollebregt

The main subject of the panel was: "3D Printing in Hospitals: Where Are We Heading?" and the topics discussed were 3D Printing costs, quality and regulation, and the need for clinical proof of the benefits of 3D Printing in healthcare. The concept was to use live polls in which the audience could answer a series of questions and see the live results onscreen. For each topic, quotes were selected from medical literature in order to start each discussion with the speakers.

Before getting to the issues, Prof. Vander Sloten took a quick survey of the professional diversity of the audience. The majority of voters were in the 3D Printing industry at 53%. The remaining specialties, research, radiology/imaging, surgeon/interventionalist and hospital management scored 24%, 9%, 8% and 7%, respectively.

Prof. Vander Sloten then asked a second question: what, in the audience's opinion, is the main challenge when implementing 3D Printing in hospitals? About half of voters selected cost/revenue as the main challenge.

Is cost a barrier to 3D Printing?

Dr. Morris opened the discussion on costs for hospitals, by expressing that cost is indeed an issue, especially when people can't see the big picture. Hospitals are under pressure to show a positive margin. If it's not met, administrators cross off the negatives on the balance sheet. They won't want to pay for 3D Printing and they won't see beyond that. They want evidence.

"There's actually a lot of evidence in the cranio-maxillofacial world that it decreases costs. It saves time in the operating. Those studies have been done and yet it's still not paid for," said Dr. Morris. More studies are being done to gather enough evidence to have an ICD-10 code, which is the first step in getting paid, he explains. ICD codes are determined by the WHO. ICD 10 codes are to identify diseases, monitor the status of the patient and the outcome. An ICD 10 code is necessary for properly assigning costs related to 3D Printing. "I think this community has to do work and help funding trials and help running trials," said Dr. Morris.

“As a community we could come together to help reduce some of those barriers from the imaging company standpoint all the way through the vendors and the software we deal with. So I think all of us should have a goal of trying to create things that are reimbursable, because if it's not reimbursable you're just going to find it in large academic centers.”

— Dr. Morris

Mr. Vollebregt added that in Europe, the issue of costs is similar to that of the US. If a certain procedure requires a 3D-printed medical device, it needs to be attributed to a certain code, so that the cost can be taken out of a designated budget. If there's not a particular budget for it, that expense is the first to go. Additionally, reimbursement and cost saving is done by looking at production costs instead of looking to improve outcomes, he said.

Mrs. de Vet opined that there needs to be the right type of evidence from studies and initiatives from different parties gathered to get reimbursement, and that this should be a collaborative effort of the industry and its partners. She added that a second way of looking at funding 3D activities is through efficiency gains.

“One minute of operating theater time is 100 to $150. Every minute you save, if you can convince the administration, every minute you save is worth that.”

Perhaps not such an easy discussion, but certainly one to have. Displaying efficiencies in the hospital or in the whole value chain will be a basis for gathering evidence to get a code, added Mrs. de Vet.

Before moving on to the next topic, Prof. Vander Sloten presented the audience with a poll regarding the discussion. 44% agreed with cost is perhaps the biggest hurdle in determining whether or not to engage in 3D Printing.

Who or what should dictate regulation?

It was Mr. Vollebregt's turn to open the discussion on quality and regulation, by briefly explaining European regulation on medical devices. At the moment, he explained, everything is considered a custom-made device. But in approximately two months, it won't be so. "…With the new medical devices regulation. The definition of what constitutes a custom-made device is going to change and also there will be a specific regime for hospital-produced devices, so that will also impact severely on hospital, let's say, business of printing medical devices in-house."

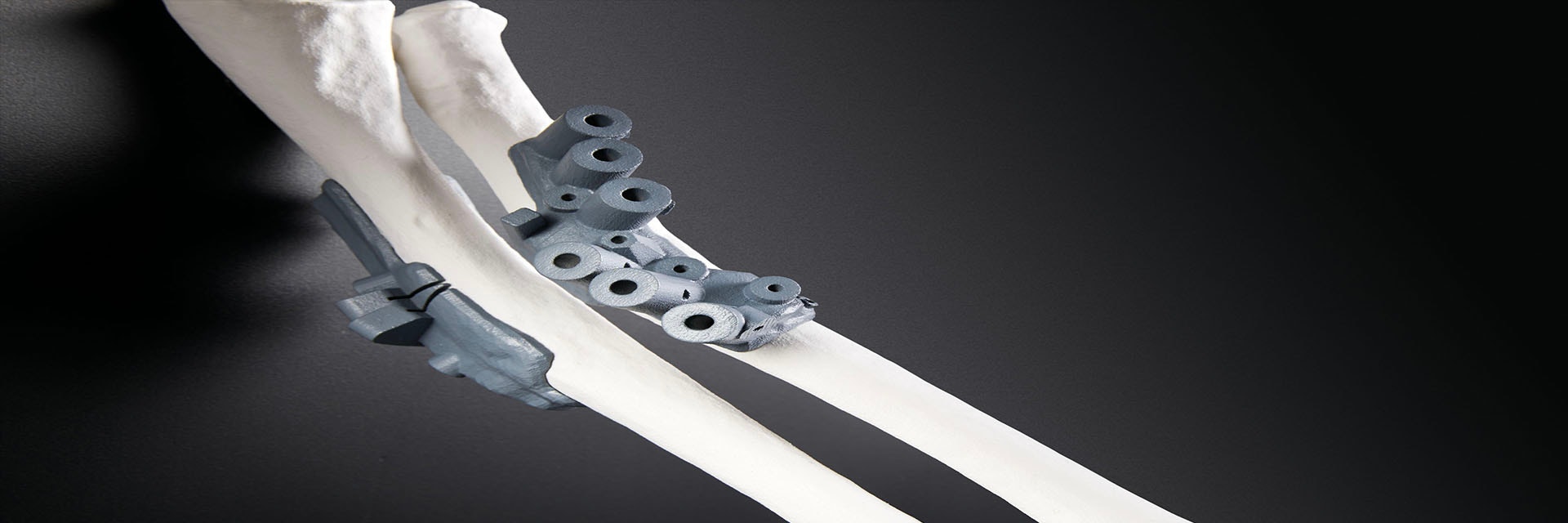

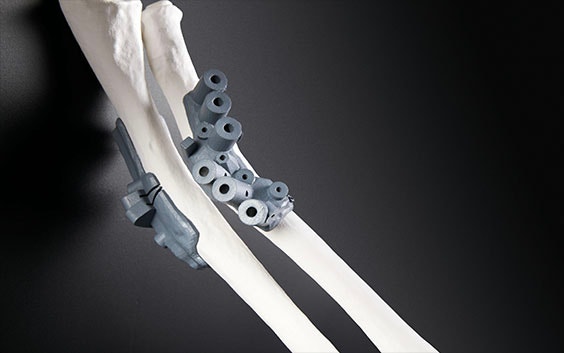

The issue to look at is the intent of the model or device. If the model would be used for planning purposes, for example, said Mr. Vollebregt, it would not need to be regulated. The safety aspects such as chemical leaks, or if it can explode, would be looked at instead. Since software is considered part of the production of a device or model, and not a medical device in itself, it would not be regulated. Only a medical device that is custom-made, such as an implant or a guide, would be regulated, he said.

Dr. Schouman gave the surgeon's perspective, as he uses 3D Printing medical devices in his hospital. He said that implants should be obtained through a very controlled way, from CT scan to print. But there are other uses for a model, he added. If the model is used to prepare implants, further discussion is needed. But if the model is used to prepare surgery, then it shouldn't need to be regulated.

“The intended use makes all the difference in the way you look at that and in the way the regulator will look at whether it’s a model or a 3D-printed device”

— Mrs. de Vet.

Another point she made is the extent to which you modify what you receive as input. The use and degree of modification will be the driving factors in deciding the regulation of 3D-printed medical devices.

Dr. Morris agreed. "I think the intended use is a big part," he said. "I think if you're going to be doing this in the hospital you need to be not only thinking about what the regulation is now but how you want these things to be made in the future. Because this community should drive regulation not vice-versa."

Dr. Morris and his colleagues have established their own regulatory system with printing in-house, he said. They have experience with materials and rely on already tested sterilizable biomaterial. They have taken steps to make sure what they make is trustworthy. He stressed that people writing regulation are not experts in 3D Printing, polymers, or titanium powders. "You, in this community, have to set these standards so that the regulatory community can come to you as experts and you help guide the regulation," he said.

Two polls about the topic followed. For the first question, "Do you agree with this statement? 'The software should be FDA cleared and the printed model should be considered a medical device,'" the Yes option got a 49% majority, Only Software got 31%, No got 16% and Only Model received 3% of the votes. "Do you agree with this statement? ‘I would install a quality system to enable my hospital to print guides and implants?’" was the second poll, and Yes came out at 58%, I'm not working in a hospital at 37%, and No at 4%.

Building the evidence in favor of 3D Printing

The third main topic of the discussion was proof of 3D Printing's added value. Prof. Vander Sloten first asked Dr. Schouman for his opinion. "It is actually very difficult to provide evidence of a benefit for the patient with a 3D-printed device in maxillofacial surgery," he said. The outcome is often more psychological than functional and is therefore very hard to measure. "There is an obvious benefit for the surgeon and for the healthcare practitioners in general. But it's really an issue to highlight the benefit for the patient."

Mr. Vollebregt saw this from a different angle, that of the evolution of 3D Printing as a production method. He believes that as long as personalized products are more expensive and complex to produce, they will remain the exception. And that if, at a future time, personalized medicine becomes more cost-effective, it will become the new standard.

Added value needs to be linked to cost efficiency, added Prof. Vander Sloten, to which Mr. Vollebregt agreed.

Mrs. de Vet offered two additional perspectives on the topic. The first was that not all 3D Printing refers to a physical model. There's great value in digital 3D Printing that can be used to optimize the supply chain and logistical process. "I think that if that then gets us to the benefits of the efficiency improvements in the workflow I think then we're at a point where this is going to be used for every single procedure."

The second point Mrs. de Vet made was regarding 3D Printing as a manufacturing technology that could possibly print devices for better clinical outcomes, at a lower cost. In those cases, why shouldn't 3D Printing be used? The answer depends on what we are talking about, said Mrs. de Vet.

"It depends," is the answer to many general 3D Printing questions, agreed Dr. Morris. It could be a specific case, or cases done routinely. In his clinic, Dr. Morris explained, they frequently print bones because they're easy to print and the guides are easy to produce. But there's a long way from a digital file to a 3D-printed model, said Dr. Morris, agreeing with another of Mrs. de Vet's statements.

Dr. Morris and his colleagues are collecting data on CMF surgeries in which 3D Printing is used in a very cost-effective way, which saves planning and operating time.

Integrating 3D Printing in these procedures has also shown better patient outcomes. "The patients are very concerned with how they look in post-procedural depression, post-procedural shame," said Dr. Morris. "That component is incredibly important and 3D Printing, at least in our shop, has helped. If we think about that stuff upfront." All the planning can be done in advance, and under one roof.

What is damaging to the industry however, said Dr. Morris, is when people try and sell the idea of 3D Printing everything for surgery. The value cannot be determined so easily, so that becomes harmful in showing good evidence.

“Evidence is going to be very important, so we can do all these things, but does it actually help improve outcomes in routine cases? We know that it does in the complex cases and I'm glad that you're collecting that evidence which is great.”

— Dr. Patel

His second point is that gathering evidence is possible but it needs to be built upon as 3D Printing labs grow in size and in numbers.

Dr. Morris made a last point about teaching surgeons. As more and more surgeons are trained to use 3D Printing in their practice, they will go work at hospitals and clinics that meet their standards. They will want to practice the modern ways they were taught, which incorporates 3D Printing.

Another poll was displayed following this third topic. The question was, "Do you agree with this statement? '3D Printing can also bring added value for routine procedures.'"

67% of the voters went for Yes, 18% chose for No, and 15% said they did not work at a hospital.

Prof. Vander Sloten closed the discussion with more live polls about the technical aspects of 3D Printing and where the 3D lab should be located in a hospital. Are you curious about the results? Or do you want to share your own opinion? We'd love to hear it.

Just like how there's a long way between a CT scan and a 3D-printed model, there's a long journey to be made from using 3D Printing in select surgeries, to making 3D Printing accessible to everyone. The good news is that evidence of cost-effectiveness and positive outcomes is building up. It's up to the community to use this evidence to lead the people writing regulations towards accepting and incorporating 3D Printing as an essential part of modern-day medicine.

Share on:

You might also like

Never miss a story like this. Get curated content delivered straight to your inbox.